Keeping It Eel: How One Historian Is Using Twitter and Medieval Factoids to Help Endangered Animals

Encounter an eel nowadays, and it’s likely in a sushi roll. Or maybe in your nightmares, inspired by the flesh-eating shrieking eels in The Princess Bride or the moray minions of The Little Mermaid.

But perhaps the creature’s reputation is in for a change. After all, unbeknownst to eels, they now have a great publicist—a medievalist who aims to transform their image from villain to environmental hero.

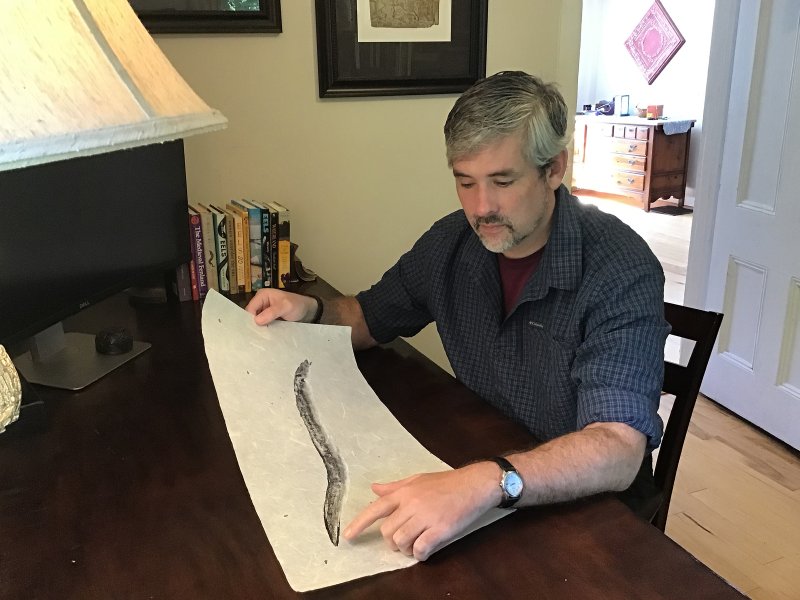

John Wyatt Greenlee, who completed his Medieval Studies Ph.D. at Cornell in May and runs what he calls “the world’s premier eel-history Twitter account,” believes that if people saw eels as part of their cultural heritage and identity, perhaps they’d be more likely to care about the animals’ future. The European eel is a critically endangered species, and as environmental advocates use World Rivers Day on Sept. 27 as a moment to talk about the importance of protecting those ecosystems, Greenlee hopes surprising stories about eels can inspire more people to get involved with such efforts.

“They’re not cute, cuddly or majestic so it’s difficult to get people interested in saving them,” says Greenlee. “The scientific community’s been trying for a really long time to convince people that it’s worth doing, but you seldom convince people by throwing facts at them.”

Greenlee had been tweeting about eels in medieval texts for about two and a half years when, at the end of 2019, his quest got a boost, in the form of a tweet about the fact that eels used to be a form of currency:

The tweet racked up thousands of likes and hundreds of retweets, was widely shared among a group of medievalists and historians who are active on Twitter, and led to some mentions on popular podcasts.

The attention has been yet another twist in the 44-year-old scholar’s surprising journey to becoming an expert on the history of eels. He calls himself the “Surprised Eel Historian” on Twitter because, as he put it to TIME, “This was not the topic I intended to write about, so I have found myself surprised to be an eel historian.”

The Age of Eels

Greenlee, a former college volleyball coach turned expert on medieval map history, got into the subject in 2015, after his curiosity was piqued by a 1647 map of London that labeled vessels in the Thames “the eel ships.”

More research revealed a backstory that involved everything from changing British demographics in the early modern period to international trade disputes. As London boomed, the city’s population began eating so many eels that the domestic stock couldn’t keep up, so Dutch imports filled the gap until the import of eels via the Thames was temporarily banned in the latter half of the 17th century during the Dutch-Anglo trade wars. From there, Greenlee’s interest grew.

In combing through medieval financial records, writing and art, going back to the eighth century, he was struck by the extent to which people in medieval England and early modern England used eels to identify themselves—a phenomenon that became the subject of his dissertation in 2017.

Scholar Thomas Bradwardine‘s 14th century book of mnemonics likens eels to England, advising readers to imagine the King of England holding in “his right hand an eel [anguilla ] wriggling about greatly, which will give you ‘England’ [Anglia ].” Family crests boasted eels. In the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts the Norman conquest of England by William the Conquerer in the 11th century, the image of Anglo-Saxon King Harold shows him above a pile of eels. An Englishman in the bottom border is holding an eel the wrong way—by the tail, rather than the head—perhaps symbolizing Harold’s hold on the English throne, represented by eels, slipping away.

But eels were more than a metaphor. In 1086, when the Normans undertook a study to figure out how people lived in the countryside they had conquered and how much it was worth, known as the Domesday Study, they collected more mentions of rents paid in eels than any other in-kind tax. When the survey was conducted, the English likely owed some 500,000 eels in taxes to landlords around that time. As part of his dissertation research, Greenlee created an interactive map of eel rents paid between the 10th and 17th centuries, and used the British Archives’ medieval currency converter to calculate what eel rents could mean in today’s dollars. He estimated at one point that an Amazon prime membership, for example, would cost between 150-300 eels.

Many landlords collecting rent payments in eels were monasteries; being paid in eels meant the monks would have enough fish to eat during the Lenten season when they couldn’t eat meat. The fish was thought to be the perfect food to eat to suppress sexual thoughts during this fasting season.

Eels were also valuable to nobles, who ordered tens of thousands of eels for feasts. Eels were “the most commonly served freshwater fish in noble English households,” according to Greenlee. Henry I loved eels. Henry II gave his otter hunter a piece of property on the condition that he could stop by for meals of eels.

The 1348-49 outbreak of the Black Death may have been a factor in an over 90% decline of English eel-rents due annually between the 13th century and the 14th century. The population had declined, land-use norms had changed and other sources of protein like beef, pork and mutton were more readily available. The Netherlands, meanwhile, got into the eel-trading business partly because the plague had driven people away from outbreaks in the Dutch countryside, allowing businessmen to buy up abandoned swampy spaces that made friendly habitats for eels.

Greenlee found eels in every aspect of life. “Medieval England had an eel culture in the same way we think of England having a tea culture,” he says.

He found medieval European recipes for eel flan, minced eel pie and eel broth. The English made wallets, clothes and wedding bands out of eel skin. Medieval medicinal remedies suggested snorting eel skin to stop bloody noses. A remedy for perking up a tired horse called for a rather unsavory use of a live eel. Eels were commonly the subject of jokes, from sexual innuendos to religious insults. In addition, eels appear in Shakespeare’s writing more than any other fish.

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

Before They Slip Away

Today, for Greenlee at least, the eel culture endures. Strangers send him stories about eels or photos of eel oddities—canned eel, eel jerky, a deodorant labeled “free of eels”—and someone even sent him hand-sewn masks with eel illustrations for his wife and two sons. And, as his Twitter feed began to accumulate more followers, he realized his research could be put to use beyond scholarly circles.

Since the early 20th century, the European eel population has been in decline, a shift attributed largely to industrialization, especially the draining of wetlands and the addition of new barriers to fish migration. A century ago, eels made up about half of the fish by weight in most European waterways. Today, while it can be hard to generalize about the status of the eel worldwide—there at least 16 species that can be found in 150 countries—they face many of the same problems as other migratory freshwater fish. In July 2020, the World Wide Fund for Nature reported that migratory freshwater fish species have declined by 76% on average over the past four decades, and by 93% in Europe in alone, due to hydropower, overfishing, climate change and pollution.

Wildlife trafficking also threatens the health of the eel population and the health of the human population too. The European eel is one of the world’s most smuggled animals, fueling an illegal trade worth more than $3 billion, and the Europol wildlife crime division estimates that more than 300 million glass eels are smuggled from Europe to Asia each year. Nick Walker, a conservation biologist and director of Eel Town, a non-profit for the conservation of freshwater eels, credits Greenlee with raising awareness about “the importance of eels to humans throughout history, especially in medieval Europe.”

This framing could be vital to their future, as for years conservation advocates have known that “charismatic megafauna”—mammals that look cute and cuddly—draw in donations that don’t often accrue to the protection of less-charismatic species. Like, say, eels.

The stakes are high. As Walker points out, it’s clearer than ever that wildlife trafficking of the sort that harms eels is dangerous—the zoonotic origins of the novel coronavirus raised awareness of the connection between the animal trade and human health—and also that eels play a key role in keeping ecosystems healthy. For example, in the U.S., Eastern elliptio mussels, which act sort of like water filters, disperse themselves by hitching a ride on American eels.

“Eels are a very important part of a fully-functioning freshwater river system,” says Andrew Kerr, chairman of the Brussels-based Sustainable Eel Group. “You take the eel out, and you completely disrupt the food chain. Eels are a moving protein of very nutritious fat that many species feed off and they in turn feed off others.”

Recently, some crackdowns on trafficking and increases in population growth, following efforts to recreate wetlands and remove dams, have given eel-conservation advocates hope.

As for Greenlee, while he works on figuring out his post-doc academic career, he’s homeschooling his kids and keeping the Twitter account active, and looking for a publisher to turn his eel history dissertation into a book. “People all over the world eat eels. So focusing on this fish in this one place in this period of time is a way of getting people to think about culture more broadly,” he says. “Historians, at a basic level, are storytellers, and you tell an interesting story by getting people to relate to the topic.”

And there’s plenty of story to tell. As he puts it, eels aren’t just vital to their ecosystems, but also to the “story of who we are.”

拡大

拡大 Eel fish, although it is mainly to be found in Asian regions, eels have been a world wide consumption commodity. Most people avoid eating it due to its resemblance of a small snake, but many are enjoying eating eel. Are you one of them? If your answer is yes, then you are in luck. Many kinds of research have found various health benefits and that eels contain nutrients that are higher than any types of meat.

Eel fish, although it is mainly to be found in Asian regions, eels have been a world wide consumption commodity. Most people avoid eating it due to its resemblance of a small snake, but many are enjoying eating eel. Are you one of them? If your answer is yes, then you are in luck. Many kinds of research have found various health benefits and that eels contain nutrients that are higher than any types of meat.